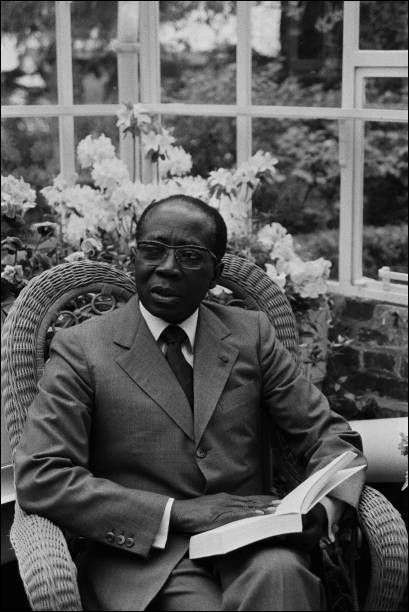

Senegal-born Léopold Sédar Senghor (1906-2001) left a profound mark on the intellectual, cultural and political history of the 20th century. His thought, which has not left the generations born in the wake of independence indifferent, has been widely discussed, criticised and commented on in successive rereadings of history. For some, he is first and foremost an essayist, a poet, an intellectual, a great defender of the French-speaking world and the first African member of the Académie française. “My poems, that’s the main thing”, he liked to say. For others, he was a former tirailleur, a French and Senegalese statesman, first a minister, councillor and member of parliament in France before the independence of his native country, and who became the first President of the Republic of Senegal (1960-80). While his supporters see him as a symbol of cooperation between France and its former colonies, his detractors see him as a symbol of French neo-colonialism in Africa. For others still, he is, along with Aimé Césaire (another famous French writer and politician from Martinique, 1913-2008), one of the pioneers of negritude, the political and literary movement that militated for an African presence throughout the world, defending the idea of “cultural crossbreeding”. Senghor said: “Negritude is the simple recognition of the fact of being black and the acceptance of this fact, of our destiny as black people, of our history and our culture”. And finally, for others, he was a tireless promoter of African arts in Africa and elsewhere, during the effervescence of the early post-colonial years. Léopold Sédar Senghor was all of these things.

When Jean Gérard Bosio, a former cultural and diplomatic adviser to the Senegalese presidency in the 1970s and 80s, donated his work to the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris in 2021, the Paris institution decided to honour this man, famous in more ways than one, 22 years after his death. Organised in six parts, the exhibition entitled Senghor and the arts. Reinventing the Universal features a wide range of items: previously unpublished archive images, photographs, film extracts, art books, paintings, lithographs, exhibition posters, illustrated poems, multimedia and sound installations, from the museum’s collections, from a donation by Jean Gérard Bosio and from Dakar. Without seeking to praise or rehabilitate him, or to produce a hagiography or even a biography, the choices made by the three exhibition curators invite us to truly rediscover his artistic and intellectual adventure, set in the historical context of the time, Senegal’s independence. “The Musée du Quai Branly’s aim is also to pursue the questioning of the Senghorian legacy that has already been addressed in past exhibitions, such as Présence Africaine, presented in 2009-10, and Dakar 66, Chroniques d’un festival panafricain, presented in 2016, which illustrate the continuity of the Paris museum’s work on the cultural history of the African continent, in order to give shape and substance to a refocused and rebalanced account of the history of world art,” explains Sarah Frioux-Salgas, associate curator of the exhibition.

Let’s take a closer look at the six parts of the exhibition through the key moments:

1) An African writing of history: As early as the 1930s, Senghor began his intellectual and political career by taking part in international discussions denouncing racism, colonisation and segregation. In 1966, in Dakar, he organised the first World Festival of Black Arts on African soil, organised by Africans, to demonstrate the vitality and excellence of African culture and to give the continent’s heritage in general, and his country’s heritage in particular, its rightful place in the history of world art.

2) Contemporary African creation: President of Senegal, Senghor implemented a strong cultural policy that was unprecedented among newly independent African countries. More than a quarter of the State budget was allocated to education, training, culture and contemporary creation. Institutions for training, creation and dissemination have been set up for the plastic and performing arts in fields as varied as painting (the Dakar School of the Arts), tapestry (Manufacture nationale de la tapisserie de Thiès), theatre (Théâtre national Daniel-Sorano) and cinema.

3) A civilisation of the Universal: By advocating the de-Westernisation of the notion of the Universal, Senghor proclaimed negritude as the “humanism of the 20th century” to combat identitarianism and imperialism. “It is a question of all of us together – all continents, races and nations – building the civilisation of the Universal, where each different civilisation will contribute its most creative values because they are the most complementary”, he claimed. Through the medium of art, the Musée Dynamique, created in 1966 as the largest museum to be built on the African continent, which hosted groundbreaking exhibitions in the 60s and 70s, notably by Picasso, Chagall, Soulages, Manessier and Hundertwasser, was part of this “rendez-vous du donner et du recevoir”, as Senghor put it in his poetic works as a metaphor for the exchange and dialogue of cultures.

4) A cultural diplomacy: Senghor saw Senegalese artists as ambassadors for his country abroad, whether actors, musicians or visual artists, contributing to the development of cultural diplomacy. These include the organisation of exchanges of objects with France (26 pieces kept in the museum of the Institut français d’Afrique Noire in Senegal, compared with around fifteen French tapestries), and the training of artists, craftsmen and cultural players such as the curator Bodel Thiam at the Neuchâtel museum, artist Mamadou Wade at the Manufacture des Gobelins in Paris and the Sourikov Institute in Moscow, art critic and museologist Ery Camara at the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, the Paris version of the exhibition L’Art nègre. Sources, évolution, expansion at the Grand Palais in 1966, the performance of Macbeth by the Sorano troupe at the Théâtre de l’Odéon in 1969, the L’art sénégalais d’aujourd’hui exhibition at the Grand Palais in 1974 and the dynamic museum lent to Germaine Acogny and Béjart to create Mudra Afrique, which later became the École des sables.

5) Dissidence: In 1974, the artist Issa Samb, who had trained at the Institut national des arts du Sénégal, burnt his paintings selected for the Art sénégalais d’aujourd’hui exhibition at the Grand Palais. He denounced the institutionalisation of art in Senegal and refused to allow his works to illustrate negritude and its political ideology. That same year, he founded the Agit’Art laboratory in Dakar, alongside artists such as El Hadji Sy. Attentive to the international avant-garde, the members of the laboratory rejected the formalism of the École de Dakar, and advocated the ephemeral, the decompartmentalisation of disciplines and the collective dimension of creation. Still active today, Agit’Art perpetuates the spirit of its founders and continues to question the place of the artist in society.

6) Legacies: From 1973 onwards, Senghor set about creating a vast cultural complex, the heart of which would have been a museum designed “to be one of the most important museographic institutions in West Africa”. This last major Senghorian project, supported by UNESCO, was to house objects of ancient and contemporary art, elements of the prehistory and history of traditional Africa, works from the IFAN museum collection (Institut fondamental d’Afrique noire, a structure dating from the colonial period), Senghor’s personal collection, loans from foreign museums and new acquisitions. The project, which was finally abandoned in 1980 when Senghor resigned, was to have been called the “Museum of Black African Art”. It was eventually renamed the “Museum of Black Civilisations”, a name now borne by a major museum in Dakar that opened in 2018, an unfinished project of Senghor’s, with no permanent collection, but which defends the same pan-African ambition.

In short, “No one has the right to erase my culture, because a community without culture is a people without human beings”, as Léopold Sédar Senghor once said.

Text by Christine Cibert.